Website accessibility is one of the most important, and often overlooked, topics for any business that has a website. As any brick-and-mortar retail business can attest, accessibility of their stores is not something that can be considered secondarily, it is paramount to a functioning business. The same is true for your online presence, and this guide will help serve as a primer for website accessibility and what you need to know.

What is website accessibility?

Website accessibility means that people of all abilities can access and use your site. In a nutshell, website accessibility means that a website and any associated tools or technologies are designed so that a website’s content is accessible to everyone, despite any physical or mental disability or impairment. Accessibility also relates to visitors being able to successfully understand or perceive the website and its content. It means that when someone looks at the web page, they can easily understand what it’s about and what they are meant to do next.

Your web design and functionality should consider: visual, auditory, cognitive, neurological, and physical disabilities. The types of devices visitors utilize to access your website can also affect their experience.

Here are a few examples how different visitors may be impacted by website functionality:

- Blind, low vision or colorblind visitors may be impacted by brightness, contrasting colors, magnification, and captions for video. These visitors may use screen readers or other tools to enlarge text when viewing your site.

- Hearing impaired visitors benefit from captions, transcripts or sign language interpretation for video and audio content.

- Those with injuries or disabilities that impact mobility may need alternative ways to navigate and use a website. Making sure the structure and order of your navigation and that your site is navigable using a keyboard are important for these visitors.

- Individuals with cognitive impairments benefit from webpage designs with bold labels, clear and organized content, and the ability to stop flashing images, carousels or scrolling content.

Website accessibility and the law

In the U.S., all federal, state, and local government websites must meet Section 508 standards. This also encompasses any business that is tied to the federal government through the products or services that they offer. As an example, real estate sites that help provide access to housing could be grouped under this banner.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) has been in place for decades and was created to provide equal opportunities for people with disabilities. While website accessibility isn’t a part of the ADA in the U.S. yet, there is a strong possibility that it may be in the future. It’s also important to recognize that different states and countries have their own rules in place for the civil rights of people with disabilities, so checking areas that apply to your business is important.

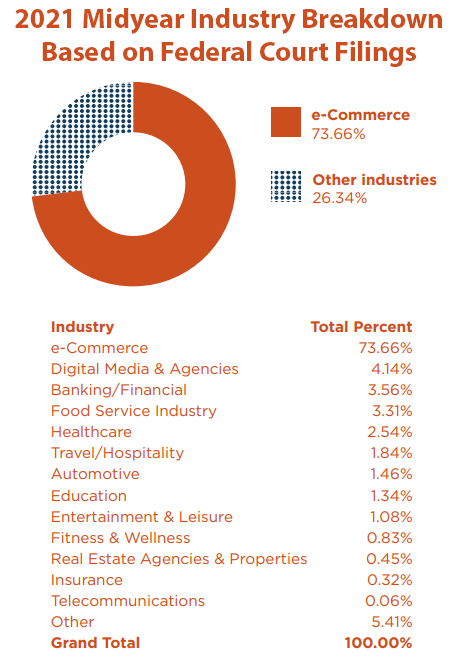

Oftentimes, people aren’t aware of the components of their website that need to be improved to meet standards until they receive complaints or legal action on behalf of a plaintiff that was unable to use their site. Usable.net publishes an annual report on accessibility lawsuits and in 2021, 74% of such lawsuits were filed against e-Commerce sites. Some lawsuits even seemed to be attracted by usability overlays, which are scripts that are often sold on the basis that they detect and fix accessibility issues. From the report: “Around 100 Companies received lawsuits after investing in widgets or overlays, some lawsuits even listed widget features as an extra burden.”

Accessibility is a topic that’s under the legal spotlight and is changing all the time. Reviewing your website for accessibility regularly, keeping track of any updates to guidelines, and making necessary changes will keep your website in compliance and enable all visitors to fully use your site.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) are a set of technical guidelines for website accessibility, published by the Web Accessibility Initiative. This is a subgroup of the World Wide Web Consortium (WC3), which is a non-profit, international community that aims to make the web a cohesive and accessible place.

As it sounds, these are guidelines, not laws – however, WCAG guidelines are frequently referred to as the standards to aim for. They have three different success levels:

- A, which is the lowest rung and easiest to meet

- AA which is of medium difficulty (and often a suggested minimum standard)

- AAA, the strictest standard which requires the most effort to meet

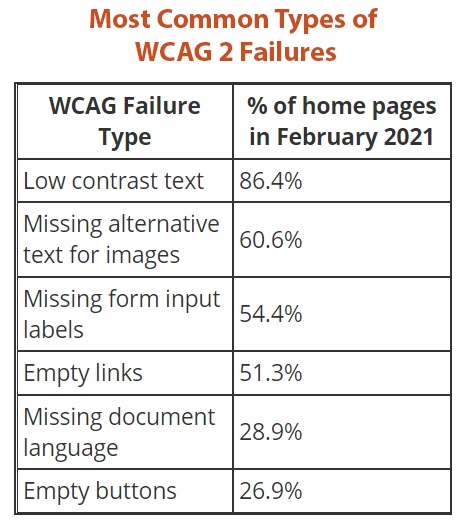

There are two versions in play at the moment, with WCAG 2.0, and WCAG 2.1 which was published in 2021. Under 2.0, 38 criteria make up the AA success level, while 2.1 adds 12 new criteria for a total of 50.

How to design an accessible website

Where should you begin when it comes to designing or measuring a website for accessibility? We recommend trying to meet as many of the WCAG criteria as possible. Below is a list to help you get started and we also recommend using one or more of the many free online tools to assess your site to see where your site is performing well and where there are opportunities to improve your site’s accessibility.

Reviewing your website for accessibility

Here are a few places to check on your site to make sure appropriate information is entered and structured:

- Alt tags: This is a text entry tied to your website images that describe the content of the image for people who can’t see it. Alt tags can also be used for SEO purposes. Make sure every image on your website has an appropriate alternative text. The WCAG guidelines state: “The text should be functional and provide an equivalent user experience, not necessarily describe the image. (For example, appropriate text alternative for a search button would be “search”, not “magnifying glass”.)”

- Page titles. These help to orientate your website users. Titles should briefly and adequately describe the content of the page and distinguish it from other pages on your website.

- Headings should use a meaningful hierarchy, from H1 on downward. It is also recommended that they are created as hyperlinks so that people can skip to the appropriate section more quickly.

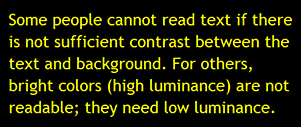

- Color contrast. Many people will be unable to read the text if the contrast between text and background is insufficient. For example, grey or yellow text on a white background isn’t visible for most visitors. For some people with reading disabilities, bright colors used for text can become illegible. A way to check this is through the contrast ratio. By default, there is a minimum webpage contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1 for normal-size text.

- Text enlarge. Many users need to be able to enlarge text size to read it, however, there are a lot of websites that don’t work well with enlarged text. Sometimes chunks of the text aren’t visible or horizontal scrolling is required to read it, another barrier for many with disabilities. Check that your text enlarges and renders well for the viewer, including usable buttons and form fields.

- Keyboard access. Some people cannot use a mouse and need to browse websites with a keyboard. This means your site should be workable by tabbing to all elements and being able to hit enter to navigate to a different page.

- Moving or flashing content. Users need to be able to control content that moves or flashes, such as carousels and scrolling news feeds. They should be able to pause or stop any movement on their own.

- Multimedia alternatives. Consider how someone who is deaf or blind will be able to consume the content within videos or podcasts. Delivering alternatives, such as transcripts and subtitles for audio content and audio content to supplement visual content is important so all visitors can access and understand the content.

- Linearized structure. Most websites are made up of rows and columns of content, however, it’s not how everyone always interacts with them. For example, someone who is blind might use a screen reader that reads the content in a linearized way. It’s important to be sure that when your website is linearized the content makes sense in the order it is shown.

Tools for measuring website accessibility

There are a variety of free online tools available to help you assess your website for accessibility. WC3 keeps an extensive list of web accessibility evaluation tools. Some we use include:

- Google Lighthouse – This is an auditing tool for accessibility, SEO, performance, and more. Lighthouse will perform a check and assign your website a score out of 100 for accessibility, along with a report with detailed information on how that score was determined.

- Contrast Checker – This WebAim tool is easy to use and allows visitors to input the HEX codes for your foreground and background colors to give you the contrast ratio. It will also show you what normal and enlarged text will look like and if your site meets meet WCAG AA or AAA standards. This tool can also be helpful if you create graphics for social media and other imagery applications.

- Pericles: Text to Speech Screen Reader is Google Chrome extension that reads the content of your website and helps you learn the order and information which is shared when screen readers process your web page and site. There are many other free text to speech readers available, as well.

- Accessibility Checklist – This is a free, easy way to view all of the latest accessibility guidelines within one checklist.

Usability testing

Tools and automated testing are helpful, however, it’s also important to test the usability of your site with your website visitors. The advantage of testing with real people is that you can see how they truly interact with your website, allowing you to discover any issues that may not have been picked up through an online tool.

When you undertake usability and accessibility testing, it’s important to test on a range of people who may experience your site differently. WC3 recommends that your testing involves:

- including your target audience and users of varying abilities

- including users throughout the development process to complete sample tasks on prototypes so you can see how different aspects of the design and coding could be improved

- discussing and addressing any accessibility questions that arise

WC3 also shares it’s important to carefully consider a range of input. Avoid falling into the idea that one person with a specific disability will be able to speak for all people with the same disability. Visit WC3 for additional resources regarding finding users and conducting usability testing.

Once you’ve completed the process, you’ll want to combine the information you get from user testing with the reports from your accessibility review.

Accessibility best practices

The topic of accessibility covers a wide range and it’s a good idea to take your cue from your testing and reviews. You may be able to identify some low-hanging fruit to start with to improve your site’s accessibility. Here are a few common best practices for accessible websites:

- Always include alt text in the markup for all images. Give more extensive descriptions for complex images.

- Don’t rely on color as a navigational aid. For example, if the only thing visually distinguishing a link is its color relative to surrounding text, users who are color blind or visually impaired may not see it. The same applies for navigational instructions – someone who is color blind may have trouble with a direction for “click on the red button.”

- Make sure all links make sense out of context, in case someone on a screen reader encounters the link out of order.

- Provide transcripts for audio files, such as podcasts.

- Use conventional page structure and hierarchy. For example, page titles, headings, and text size. (Navigational text should typically be sized 16 – 18px).

- Use captioning on video content.

- Use a skip navigation feature so anyone navigating with a keyboard can skip to the section they need.

- Test your site for accessibility regularly (for example: quarterly, annually or after a redesign) and keep track of any updates to guidelines.

Final thoughts

A fundamental principle of the Web is that it’s meant to be a tool for all people. The core intention of accessibility is to remove barriers that impede people from being able to communicate, make progress, or achieve a goal. This covers many aspects of how a website is perceived, navigated, and used by visitors with varying abilities.

Using online tools, performing user testing, staying informed of updated guidelines, and making necessary website changes regularly are all good practice and important for website accessibility. This will give more people access to your site, additional exposure and potential earnings, and create an inclusive and accessible experience for as many visitors as possible.

Do you need support with an accessibility review, update or optimization of your website? Our team can help. Get in touch with us today.

Read More on Website Optimization

A Marketer’s Guide To Redesigning Your Website

These Tests Can Help You to Optimize Your Website

How to Make Sure Your Website is Responsive and Mobile-Friendly